Following on our week about historiography and before our week on public history, we looked at history and film. This was really three discussions in one, so I’m not sure how well it all meshed together: film as a historical object (i.e. film as evidence of the past); documentary filmmaking as a historical method; and the promise and perils of using films (feature films, especially) to recount historical narratives, to explicitly “tell history.” Our reading was from HistoryMatters, Tom Gunning’s marvelous and well-written “Making Sense of Films.”

Film as Evidence:

Film as Evidence:

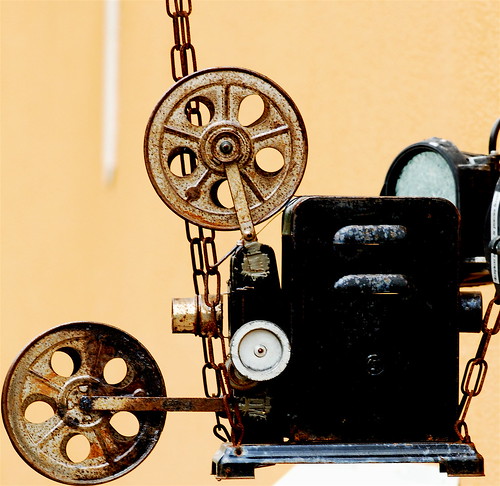

Few of my students have even ever handled a film up close. I mean a real film. For them, film is equivalent to video. And our university library doesn’t own any films in canisters or on reels. I borrowed a microfilm and brought it to class because it’s at least the same gauge as 35mm film and somewhat resembles it, although it lacks the sprockets and the frame-by-frame story. If you have access to a projector and a film, by all means: bring it and do it.

As a grad student, when I TA’d for film studies scholar Tom Doherty‘s class called “News on Screen” at Brandeis, I got to be the evening projectionist. Being something of a film purist, Doherty ordered his films as reel films because he thought (correctly, I believe) that it gave a truer, more authentic, richer film viewing experience. Big screen, dark theater, actual film projector, cue dots, the real deal. Projectionists and film buffs are a breed apart.

A few years ago my small town took advantage of the proximity of the great MIT film musicologist Marty Marks and got him to come out to give one of his live performances accompanying the Charlie Chaplin silent classic Gold Rush. It was screened in our crumbly old town hall, as a projected reel film. What a treat!

Going back even farther and here I am surely dating myself, our public library used to rent projectors and films when I was very small, I clearly remember my family checking them out and watching films at home for a treat, including an animated version of one of our favorite children’s books, Don Freeman’s Mop Top (having been a shaggy redhead myself, I could relate). Good times.

Instead, for my class, we had to make do with watching old films as digitized video and it just ain’t the same. They’re still wonderful but you don’t have the whir, click, lightbulb, vintage machine cool factor.

Last year I got our department to buy the marvelous three-disc set of More Treasures from the American Film Archives, and from that we watched a few of the early Biograph/Edison film captures in Manhattan at the turn of the last century. My students were astounded, even though the films are only a few minutes long, at what a sense of immediacy and movement there is in what the camera captures when it gets turned on ordinary streets and people. We watched some of them twice in a row just for the joy of it. We also viewed the “Great Train Robbery” on YouTube, but I couldn’t find a version that had decent music. One had a strange slow symphony behind it, while another started out promising with some ragtime tunes but then stuck in a 1920s jazz/saxophone piece which was all wrong. If you find a decently-scored free one out there, do let me know.

We didn’t have time for this one, but I would have loved to show at least part of the vintage Kodak industrial film, “Murder on the Screen,” about how to handle movie film – it’s completely charming and terrific for showing what equipment and storage/handling techniques were needed to preserve old film, and it helped me appreciate why 90% of silent films and over 50% of feature films from before 1950 are now lost. I was intrigued to learn from the Treasures book that accompanies the discs that many of these films were preserved & subsequently restored from paper prints that had been filed as copyright proofs with the Library of Congress, something I didn’t know before.

Historical Documentary:

Everyone’s familiar by now with the distinctive documentary style of Ken Burns (and in the week that we were talking about this, his multipart Civil War was just starting over again on PBS), and the way that his style has profoundly shaped public understandings of the topics he treats and what people have come to expect from a documentary. It’s long-form storytelling with a terrifically tuned eye to what will be palatable to mass American audiences. Not everyone loves it, or thinks it’s good history, and I had my students read some critiques of Burns’ documentary approach to give us some fodder for discussion about what the possibilities and the limitations of the genre might be. (Links at the original post).

Films that Tell History:

The very morning I was set to talk about this subject, I got a mass-mailing email from the production house that made the newly-released film The Conspirator, praising me as an “influencer” and recommending that I support and promote their film because it tells a “historically accurate” story and drew on the input of scholars in its construction and offers on its promotional website some relevant educational materials. I have yet to see the film but I did screen the trailer with my class and we talked about why there is a perceived market for cerebral and/or pedantic history “art films” of this sort, ones that claim to prioritize accuracy over commercial values and Hollywood endings.

Finally, I wanted to screen something in class that I could show in 2 film versions: a documentary treatment and a feature film treatment. There are lots of possibilities I could have chosen, but I finally settled on the 1913 Washington DC parade for womens’ suffrage organized by Alice Paul. I showed two clips in class for side-by-side discussion: one from the PBS documentary One Woman, One Vote and the other from the HBO feature Iron-Jawed Angels. Although they depict the same event and actually contain a lot of the same historical details, they’re quite different in construction, sound, tone, and effect. The use of a contemporary soundtrack in the HBO film (Lauryn Hill’s 1999 “Everything is Everything,” fading into Hildegard Von Bingen singing “Vision O Euchari in Leta Via”) is quite striking and I can never decide if I agree with the decision to use it or not. It drives me crazy at the same time I admire the sentiment behind the choice. Where the documentary relies on a voice-over to describe the action and orient the viewer, the HBO version shoots in color, at street level, with gratuitous use of slow motion for a greater sense of chaos and confusion, purposely disorienting viewers and tilting them into the crowd. It made for an effective class discussion to have the same event rendered in nearly opposite ways and we got a lot of mileage out of contrasting the two and discussing the filmmakers’ intentions and results. Which was more effective, which was more accurate? Are those even the right criteria?

Image credit: By pedrosimoes7, used under Creative Commons license

Great posting on a lot of interesting ideas – I’ll proffer my two cents on the music choices in films, particularly ‘Iron Jawed Angels.’ For some reason, and maybe I shouldn’t get so upset about it, but for the most part, anachronism in film bothers me. You asked whether the HBO producers’ decision make sense, I’ll say no. There are cases to be made for discordant music with on screen imagery – I’ll point to Spike Lee’s decision to use Aaron Copeland in ‘He’s Got Game,’ but the soundtrack in ‘Angels’ struck me as choice made to ‘make things contemporary’ and not necessarily in a good way.

I’ve mixed feelings about Burns, but part of that is understanding that his details depend on the expected knowledge of the audience. The War and The Civil War are more “personal” (in the source for his stories, primary documents though they may be) because he expects the audience to know the basics as plenty of others have covered them.

National Parks (my personal fav work of his) on the other hand was a subject that few people actually knew anything about and so was covered with a lot more depth with only a few personal stories that added color to it, rather than a documentary of all color resulting in little lasting substance. Its important to know what people thought and how they felt about the facts of the era, but not to the distraction of losing sight of the facts of the era in the process. I think National Parks struck the perfect balance.

I just went through watching Alastair Cooke’s America for the first time since I was, well, 10. That, like the contemporary Connections (James Burke), was for years the definition of the proper history documentary for me. There’s a direct honesty about it (something perhaps only an outsider like Cooke could have gotten away with) that’s rather refreshing, particularly in topics like the Mormons and the founding of Utah (part of the shaping of the West ignored by most other documentaries – I note “The Real West” completely ignored the subject), the rise of Progressivism and the betrayal of the movement by Taft (as perceived by Teddy), and the true cause of the depression. I have never seen an American documentary that actually talked about Hoovervilles, yet I’ve seen 2 British ones (and even a Doctor Who episode) cover them.